We got an interesting request a couple of weeks ago from Chris Gabriele, a whale biologist at Glacier Bay National Park: would we be willing to come out to the park and help give flukes to a tail-less whale?

Snow was a humpback whale first identified in the waters of Glacier Bay in the 1970s. She was struck and killed by a cruise ship in 2001. Local volunteers and GBNP personnel cleaned and collected her bones and sent them off to be re-articulated by a company in Maine. In 2014 the bones returned to Bartlett Cove, where they were put on display. The huge skeleton, about 45 feet long, is a wonderful addition to the park. It’s strange and beautiful and awe-inspiring, and thousands of people marvel at it. I always spend some time looking at it when I’m out there; I posted some sketches and thoughts about it here.

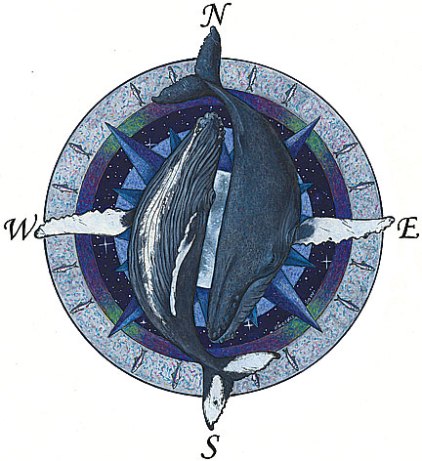

But for many people, there is something missing–some satisfaction absent, a question un-answered: where are the flukes? Flukes are perhaps the most iconic parts of whales–especially of humpback whales, who often lift their flukes above the water’s surface. But there are no bones in whale flukes; their shape is created by dense, fibrous tissue covered with fat and skin. So as interesting as Snow’s skeleton is, it feels out of balance, somehow lacking, without the flukes.

Hence Chris’s request. Could we somehow add flukes to the skeleton display? There had been a lot of talk about ways to do that; one idea was to outline them with metal on the skeleton somehow (that’s what was done for the killer whale skeleton at the Gustavus library). But Chris felt (and we agreed) that the bones should speak for themselves–the flukes should be subtle. How about creating an outline of them on the ground below?

We started with a photo of Snow’s flukes, plus their dimensions (measured when she washed ashore). First we calculated where the flukes would lie, in relation to the skeleton. Then we measured out the flukes’ 15-foot-plus width, tip to tip, and their 3.5-foot depth, and marked the tips and notch with stones. We laid the rope out to “sketch” the shape on the ground, then dug a little trench to draw the outline. Next we were off to the nearby beach with a bucket, to gather golf-ball-sized granite stones, which we hauled up to the work site and set in the trench, forming a pale, pebbly outline.

It looked pretty good, but felt incomplete somehow. Perhaps we should fill in the outline… we went back down to the beach and gathered buckets of coarse sand, poured it in our stony outline, smoothed it, and stepped back… Perfect! The dark sand, peppered with white shards of barnacle shells, created a subtly different value and texture below the skeleton: the shadow of Snow’s long-gone flukes. In the photo above, the caudal bones are just above the edge of the picture.